The Anti-Politics Of Popularism

The current strategy to bring Democrats back from the brink of electoral wipeouts rejects the very thing they need most

A growing group of pundits and pollsters is warning that Democrats are heading towards an electoral wipeout that could lock them out of power for at least a decade. Continued education polarization combined with decreasing racial polarization driving moderate and conservative-leaning Latinos towards Republicans, not to mention gerrymandered districts and a Senate and electoral college map that magnify the political power of Republican voters, are brewing a particularly nasty storm that could soon lead to an extended Republican trifecta in Washington.

This would be quite bad for the country. What little Republicans have said about what they plan to do with control of the federal government reveals an agenda dead set on making life worse for the poorest and most vulnerable Americans. Even worse, a large fraction of Republicans are open to subverting democracy altogether, taking inspiration from Hungary where reactionaries have undermined free and fair elections, an independent judiciary, and other liberal institutions to the point of uselessness.

So what to do about this impending disaster? Some data-informed pundits have a theory of the case. Democrats need to win more non-college-educated white voters, particularly those that wield outsized political power in rural states. To do that, they need to adopt policies and messaging that this conservative-leaning group and the country at large find appealing. This theory is otherwise known as “popularism.”

On its surface, popularism is intuitive political advice: do things voters like, and they’ll support you. But interrogating this theory reveals at best some glib recommendations of generic political best practice and at worst, nebulous advice that boils down to some form of “do nothing at all.” It turns out that conservative-leaning white voters mostly prefer the status quo. Even popular policies, like broadly agreed upon gun safety legislation, become less popular if voters see them as a change in current policy.

Voters punish the political party they see as stirring up too much conflict, and the messy process of negotiating policy often turns what once were popular ideas into political liabilities. The best thing for the party in power to do, the theory goes, is to quietly pass some noncontroversial legislation and probably make sure gas prices stay low for good measure. The American public, after all, has an uncanny ability to accommodate just about anything if given enough time to adjust.

Some have even argued that preserving the status quo should be the explicit goal of the Democratic Party. If the choice is between the status quo and democratic backsliding, the current situation is obviously preferable, however inadequate it may be. This argument has some merit. Democrats can and should do everything they can to stave off a Republican takeover of government, including running more moderate and heterodox candidates in rural areas, even ones that don’t affiliate with the Democratic Party. In the short term, holding a few crucial seats to stave off a Republican supermajority in the Senate has obvious advantages.

But this is not a viable long-term political strategy. The more that popularism comes to dominate Democrats’ strategic guidance, the more it threatens to hinder their long-term goals of equality and justice. Taken to its logical conclusion, popularism does away with politics altogether, replacing it with a rote system of calibrating to poll responses at any given time. Since voters prefer stability over ambition, winning elections, not wielding power, becomes the ultimate goal.

While center-left stability is obviously preferable to unchecked right-wing ambition in the short term, it’s hardly a recipe for progress. In fact, it’s caused its own fair share of backsliding. The anti-politics of the popularists echoes back to the 1980s, when a group of moderate Democrats thought they could triangulate between the ascendant conservative right and declining New Deal liberalism by forging a “third way” that rejected both.

As historian Lily Geismer has written, Democrats elected in the 1970s responded to Carter’s failure by reorienting the party around a more market-oriented message. They had just watched a Democratic president get dragged down by rising inflation and an unpopular crisis in the Middle East. They saw a resurgent right, invigorated by a culture war fueled by gay panics, reactions against feminism, and opposition to abortion rights erode a culturally conservative Democratic constituency to win massive victories that threatened to lock Democrats out of power in the White House and Senate for several cycles. The historical rhyme here should be obvious.

Campaigning against the labor movement and Great Society, Democrats like Al Gore, Gary Hart, Dick Gephardt, and Chuck Robb built power by capitalizing on working class white voters’ penchant for anti-government conservatism that Republicans had spent years stoking. This group called themselves the New Democrats and argued that the party should drop its rhetoric of fairness and redistribution and emphasize individualism, economic growth, and the provision of public goods through private means. Core issues like welfare and civil rights were mostly absent from their agenda.

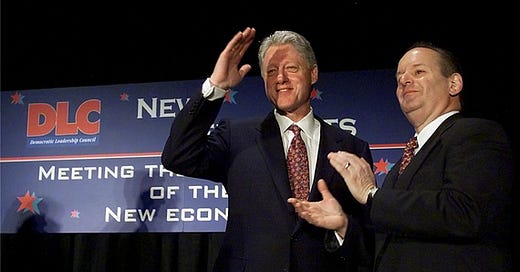

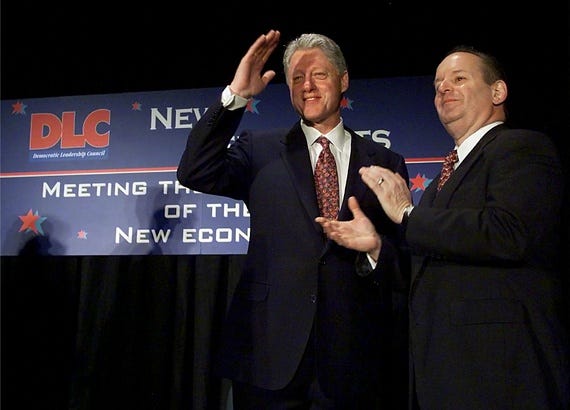

With the help of big business, the New Democrats won out. Clinton and Gore dismantled the New Deal program of Aid To Families With Dependent Children, cut food stamps, cut immigrants off from public assistance, sparked the charter school movement, deregulated banks with reforms that reverberated into 2008, signed free trade agreements that eroded American manufacturing, and undermined organized labor’s attempts to stop the economic dislocation.

People like Matt Yglesias would likely argue that a Democratic plan to end welfare as we know it is preferable to a Republican one, but just because popularism engenders a failure of imagination, doesn’t mean a better political strategy doesn’t exist.

If the polls are an accurate reflection of reality, then progressives will be consistently stymied by voters who won’t support candidates campaigning on things like a just immigration system, a sizable expansion of the welfare state, bans on assault weapons, ending the use of fossil fuels, or any number of other policies that would alleviate large amounts of suffering. Either progressive-minded candidates can start lying to voters en masse about what they’ll do when elected, or Democrats will have to start changing public opinion. The latter strategy is obviously preferable.

This is where actual politics - the business of building mass coalitions that can demand and win concessions - comes into play. What Democrats need more of, as Osita Nwanevu has written, is movement building. The best hope for reversing the societal decay driving Americans to retreat into a permanent anti-social defensive crouch, is building and strengthening organizations that can politically mobilize people to (as one big fan of movement building put it) fight for someone they don’t know.

That won’t come from a strategy that shuns the basic work of renegotiating who gets what, when, and how. Policy fights within the halls of power are important, but the real slow boring of hard boards happens before the inauguration ceremonies. Long-term success for Democrats will mean engaging with movements beyond the organizational framework of socially conscious charitable foundations and professional activist nonprofits that is itself the result of another Clinton-era policy failure. One need only look at the right’s successful politicization of gun ownership for inspiration.

Previous generations have attempted this hard work of political persuasion and succeeded, and they did it largely by engaging in what popularists disdain most: extra-electoral activism and organizing designed to change public opinion and convince those with power to deliver on new policies. As Sam Adler Bell argues, the labor movement, “a movement of the left that mobilizes and draws us together on the basis of our most basic associations and material interests,” is the best place to start. Some good old-fashioned party building to physically bring people together would help too. Republicans know this, which is why they are already doing it.

The biggest mistake the New Democrats in the 1980s made was believing they could maintain a viable commitment to the party’s principles while casting aside organized labor, the one movement that had powered long-term Democratic victories for a generation. Democrats today are on the brink of making a similar mistake, choosing to shackle themselves to conservative public opinion at the expense of building movements that can help transcend it. There’s more than one way out of the electoral wilderness, and today’s Democratic Party has the benefit of hindsight. The more that Democrats dig in for a fight to move the political landscape onto more favorable grounds, the more successful they’ll be in the long term. The anti-politics of popularism and triangulation is a dead end, but by no means are we doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past.

I really like this blog/newsletter so far. I have one request/suggestion, I’d love to see you refine your critiques further on popularists. As others have pointed out a to a degree, many of your critiques of them so far have actually been arguments with which many of them agree. I’d love to get a better sense of what the actual points of contention are, since everyone seems to agree that winning elections is important and that movement building is important. So is the disagreement about when to focus on each activity or what those terms mean or something else.

Thanks! There’s just about nothing more important to our cointe’s medium term prospects than a vibrant, successful Democratic Party.

I think the issue is that there's three distinct but overlapping points that the Matt Yglesias types (I include myself) make:

1) Politicians in an election need to win +50% support in the here and now. There's little time for persuasion during a campaign, you need to win with the electorate you have. The electorate that we have is mostly made up of people whose political views are more moderate, messy, & poorly-defined than the passionate partisans on either side. This doesn't just mean "do whatever working class white men want". Black women vote Democratic by bigger margins than anyone else, but even these voters aren't a bunch of DSA progressives & leftists. *All* demographics are mostly made up of people who aren't passionate ideologues.

2) Pundits, activists, think tanks, etc. should persuade people of what is true and right, *especially* if those positions are currently unpopular. But many of them have a bad habit of saying things that appeal to people who already agree with them, at the expense of persuading people who disagree. A lot of online sociopolitical discourse is people in the left-most 5% of the population accusing the people in the left-most 20% of the population of being "right-wing". That's not how persuasion or movement-building works. (I'm conflating "pundits and activists" with "online sociopolitical discourse" here. Maybe I shouldn't?)

3) There are many cases where progressives are wrong on the merits, where the things they say just aren't true and right to begin with. Or maybe I'm the one whose wrong on the merits! This is normal disagreement, and should be resolved by arguing back and forth in good faith.

These ideas have some overlap. All of them are some form of "Progressives are a niche group. They should listen to moderates". But they're fully independent claims. A politician will fail if they can't get +50% support. Activists will fail if they're only preaching to the choir. And of course we should figure out what ideas are true and right on the merits.